PrideBlog: Confidential news

by Conrad Breyer

German Embassy, Heinrich Böll Foundation, Tochka Opori, then our film – the program for Friday promises to be as exhausting as that of the previous days. Sleepily, we start our visit as a “Munich delegation” at the embassy – two of us this year only, no city council, no group behind us.

But basically it is also more pleasant to meet the new man in the diplomatic service. Lukas B. has been in Kyiv for a few weeks; he will be our contact person in the next years when it comes to human rights in Ukraine. The same applies to the Heinrich Böll Foundation. There, too, with Johannes V. (pictured below right), a newcomer has arrived who has yet to start. We got to know each other as a small group – the embassy served water, the foundation pizza – and we feel it: It will be a good cooperation!

What we discussed there is unfortunately confidential. But we can say that we from Munich Kyiv Queer have at least contributed to the integration of the two new colleagues from Germany. After all, after nine years of human rights work in Ukraine, we are quite familiar with the political situation in the country, especially with LGBTIQ*-issues. We were indeed able to give many valuable tips.

Finding allies while eating pancakes

In the afternoon, we meet Tochka Opori at a restaurant in Podil, an organization that deals with LGBTIQ* in general. The office shared by the five or six staff members would have been much too small for our “big” delegation, our hosts joke. Besides, the restaurant called “BlinStory” is close to the cinema where we want to show the movie “Anders als die Andern” in the evening. It is the first film ever to deal with the topic of homosexuality. The German silent film has survived only in fragments, and in Ukraine of all places. The Filmmuseum in Munich has reconstructed and restored it. But more on that later.

I ask how Tochka Opori survived the Corona period. Everyone laughs. “We don’t really know either,” says Tymur Levchuk, who runs the NGO (pictured below left). But in truth, like most other LGBTIQ* organizations, they have simply worked harder. In any case, they present us a surprising number of new ideas.

For example, there is this Allies’ project: Tochka Opori has started to look for allies for LGBTIQ* in Ukraine who are not queer. The group also has a name: “Allies in Action.” Together, they train each other in knowledge about sexual minorities, the right way to address them and actions they conduct. During the pandemic, Tochka Opori also counseled LGBTIQ* who lost their jobs. Quite a few moved back to their parents’ house, which is not easy when mom and dad are homo- or trans*-phobic. So the NGO helped with job placement – another thing we haven’t heard like this from an LGBTIQ* organization.

Brotherhoods as a model for gay marriage

Tochka Opori, in cooperation with individual deputies, has also introduced draft of bills into parliament that were intended to make the Verchovna Rada committees think twice. And in a rather twisted way. Example: “Brotherhood.” This early form of man-male civil union existed in the Middle Ages and early modern times among the Cossacks. Two men took responsibility for each other, they had rights and duties, but without having an erotic relationship with each other.

The (not entirely serious) draft law now provides for the introduction of a registered partnership based on this tradition. Churches and politicians are against it, of course, but in doing so they are somehow also going against their own traditions in the country, which the activists of Tochka Opori can use well for their political work. Complicated, but ingenious, in my opinion. The organization works a lot with politicians, who in Ukraine seldomly pay attention to the needs of the community. The fear of offending potential voters is too great. And what about the planned law against hate crimes? “We are confident that the text will pass the Rada,” says Tymur.

Different from the others – a different plan

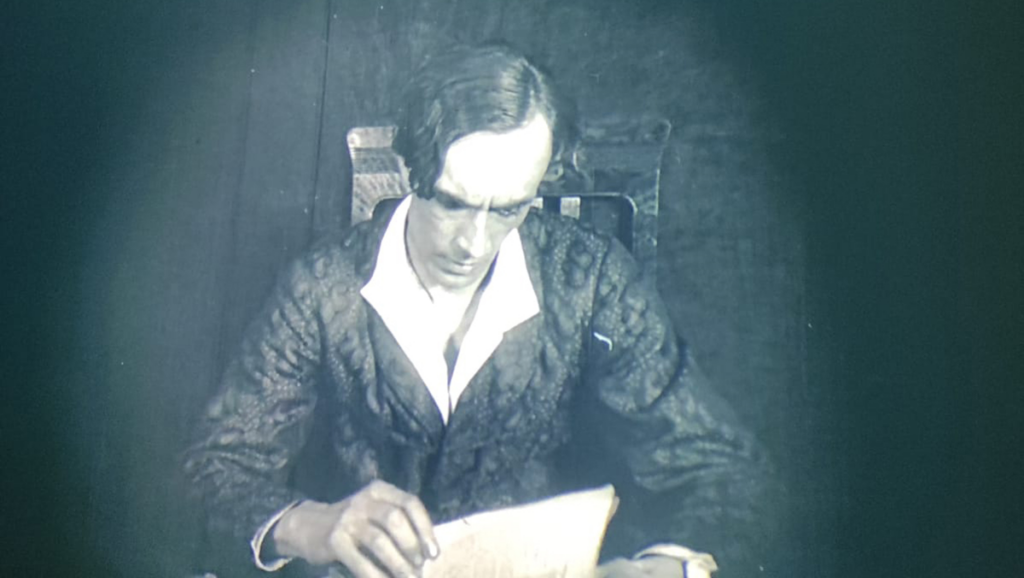

After an hour and a half of intensive discussion, we set off in the direction of the cinema to set up the technology for our film presentation and to rehearse the procedure. Tonight we want to show the silent film “Anders als die Andern” from the Filmmuseum München as described.

Kino 42 is a small program cinema, as the name suggests: more than 42 people do not fit into the auditorium. The location of the event was kept secret until the end for security reasons. Anyone who wanted to see the film had to register.

Unfortunately, it happens again and again that right-wing radicals block or storm LGBTIQ* film screenings. In the fall of 2014, some idiots set fire to the Zhowten cinema while the program was running, as the operator was preparing to screen a gay movie. Fortunately, no one was hurt. We have learned from this: There is security outside the door. It costs a few hundred euros, but it pays off. Later, I see a gay couple in each other’s arms as it gets dark in the room. Nowhere else could they do that in Kyiv.

The best crew

Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, Stefan Droessler, the director of the Munich Film Museum, could not travel to Kyiv to introduce “Anders als die Andern”. Therefore we had to improvise a bit, which the chief logistician of the Pride, Anton Levdik, endured only with humor. The museum had uploaded the file with the film on Vimeo, so we could simply connect a laptop to the cinema projector.

In the short time available, we had also not managed to replace the German intertitles of the 51-minute work with Ukrainian text. We therefore asked a narrator to read out the texts previously translated. Edward Reese from KyivPride performed this responsible task almost masterfully.

And the introductory lecture to the film by Richard Oswald and Magnus Hirschfeld was given by me personally, although I am not exactly an expert on silent films. So the circumstances were complicated, which we are used to when we work in Ukraine. But it still takes nerve.

And then – everything worked out fine. The speeches, the film screening, the recitation. We were even able to answer most of the questions from the audience, who were very interested and excited that we were showing the film in Ukraine, which – as far as I know – only very few people have seen in its most recent version so far.

After the official part we discussed for a long time with people from the audience, exchanged addresses, thought about how we could make the film accessible to a wider audience – until the cinema drove us out of the hall. There we were, exhausted but happy, standing in the street until the hustle and bustle of the nighttime Podil pulled us along. But that is another story.