We are singing for our lives! The story of Ukraine’s 1st ever LGBTI-choir

Despite her initial reluctance, Olga Rubtsova has been director of Ukraine’s first lesbigay choir, Qwerty Queer, since it was founded four years ago. These days, it is seen as a role model for other LGBTI* choirs in the country and is also famous beyond the community. The idea that led to its foundation came from Munich.

What’s Olga’s secret? She’s talented, she’s pragmatic, and on occasion she’s as stubborn as a mule. If she hadn’t singlemindedly pursued her dream, she wouldn’t be standing on the podium in the Gasteig today. Olga Rubtsova, 32 and from Odessa, always wanted to make music. But it’s something of a miracle nonetheless that she now directs a choir. The path she took to get there was anything but straightforward – not least thanks to her own mother.

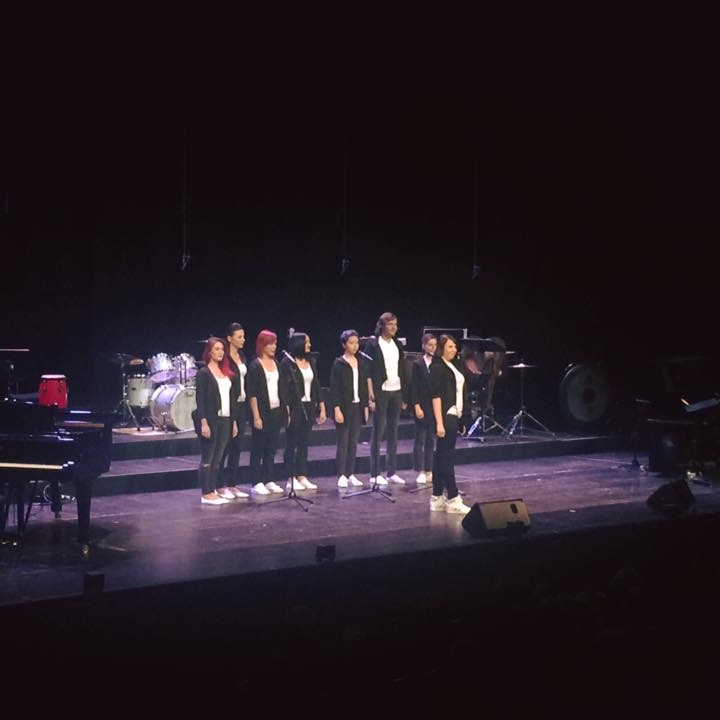

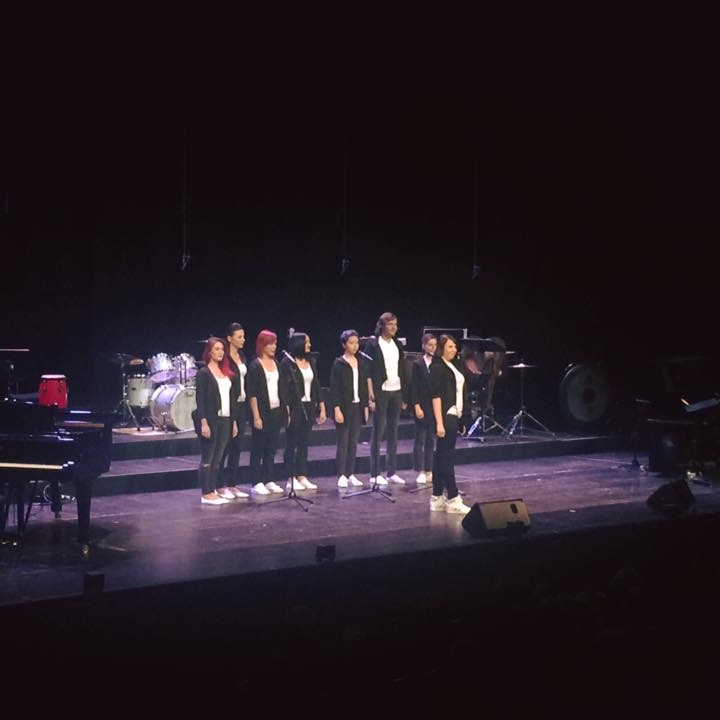

Qwerty Queer, Ukraine’s first ever lesbigay choir, is still a very young ensemble: it was born in late 2014 / early 2015 of an idea that came from Various Voices in Munich, no less. (We’ll come back to that story later.) The group’s ten core members have a repertoire stretching from pop through to folk music; they sing both political songs and love songs. Most of their tunes come from the UK, the USA, Ukraine, and Russia. And the singers are young: almost all of them are under 30.

Born in Queer Home Odessa

Every Saturday at one o’clock, Mykyta – the only man in the group – hosts a rehearsal in his flat; this can last up to five hours. Although they’re a lay choir, they’ve reached a professional standard and perform in public. For a country like Ukraine, where homo-, trans*-, and inter*phobia are still widespread, that is something that definitely cannot be taken for granted. Qwerty Queer has even featured on television. When Munich was selected to host Various Voices in June 2014, it was all but impossible to imagine any of this happening. Qwerty Queer didn’t even exist yet, but plans were already afoot.

Because in fact the Munich organisers had already got it into their heads to make a point of inviting a choir from Kyiv to the giant choral festival in 2018. After all, Kyiv is twinned with Munich – and hadn’t both cities’ LGBTI* communities agreed to start cooperating back in the summer of 2012? So it was time to act: Various Voices quickly set up a Ukraine project group, and this group seized the initiative in Pride Week 2014 by inviting Munich CSD’s Ukrainian guests to the city’s Schloss event location. Against the backdrop of a gala performance by Lilamunde – a small but perfectly formed lesbian choir that was marking its 20th anniversary – the project group put its proposal to the Ukrainians, together with an offer of support from Munich Kyiv Queer in its capacity as contact group between Kyiv and Munich.

Everyone welcomed the idea; the only problem was a lack of choirs. Until four years ago, Ukraine didn’t have a single lesbian or gay choir, let alone a bi* or trans* one. The scene was made up of political activists, and forming a leisure and self-help group was out of the question: the community had other concerns. The country’s first Pride had been held only a year earlier in 2013; advocating too visibly for LGBTI* rights is a risky business even today. But where there’s a will, there’s a way.

And so the Kyiv activists carried the idea back to Ukraine, where it came to bear fruit in Odessa. It was here on the Black Sea that Munich Kyiv Queer, which brings together activists from Kyiv and Munich, was due to put on an exhibition of Munich artist Naomi Lawrence August 2014. This was an ideal opportunity to present the Various Voices project at Queer Home, which is Gay Alliance Ukraine’s local meeting point. To whet the Ukrainians’ appetite, they offered to fly the choir that would participate in the choral festival in 2018 to Munich once each year, as a way of helping it to get going. Munich’s choirs had committed to help.

It didn’t take long to find some volunteers, and the then head of Queer Home in Odessa, Anna Leonova, already had a director in mind: Olga Rubtsova, who she knew from Queer Home. But Olga demurred: “It seemed to me to be too much responsibility,” she says today. In addition, she wasn’t even out. She managed to fend Anna off for half a year – even though Olga was absolutely destined for this role like no other.

Your mother, your destiny

In her youth, Olga had attended music school in Odessa. She had wanted to train to be a singer, but there was no room for her in the singing class. A bitter disappointment! Instead, her mother convinced her to start off by learning to play the piano. After all, Alla Pugacheva – that icon of Russian pop music – had started her career in the same way: first piano, then singing. Olga gave in. It wasn’t the first time that she’d acted on her mother’s advice – and it wouldn’t be the last. When a place in the singing class did finally come up, her piano teacher didn’t let her switch: “No-one leaves my course.” So Olga simply sang in her spare time. “It let me feel free,” she says.

It took Olga just three years – not seven! – to learn the piano. Now she wanted to attend the conservatory and at last learn to sing. But it was the same story all over again: no free places, and a year’s wait. Her mother urged her to use the time to train for a practical job, like dental technician. At least it would still involve the mouth. Once again, Olga took her mother’s advice, completed the training, worked as a dental technician, and then – again on her mother’s advice – went on to study dentistry. Oh, mother.

When Anna Leonova approached Olga, she was still in the middle of her studies. In the end, Anna caught Olga by surprise: she lured her to a karaoke evening at Queer Home with a few women who were really keen to sing in a choir. That was a smart move. It was lots of fun for everyone, and when three of them asked Olga whether they mightn’t get together now and again in future to sing together, Olga had no choice. “Really? That’s great! But you’ll have to conduct us,” they suddenly added.

And that was how Qwerty Queer was formed. Of course, it wasn’t called that yet. Where did the name come from? QWERTY is the order of the letters on US computer keyboards. When they started searching online in social networks for people to join their choir, the women ended up doing lots of typing, and that’s where they got the idea. “Qwerty” stands for the regular, the normal. “Queer” for otherness, for diversity. So “Qwerty Queer” it was, then – a part of a whole, in all its colourfulness.

Olga started rehearsing with the three women – on a voluntary basis, of course. Over time, they were joined by more women, and later men too, and their repertoire expanded. When six of them travelled to Mainz in June 2015 with their Munich counterparts for the QueerTakte gathering of south German choirs, the Ukrainian singers really impressed everyone – including Mainz’s mayor, who was in the audience for a memorable performance of some of their songs.

Leading the way as an example to others

Qwerty Queer has now made three trips to Munich; in 2016 the group even co-organised the major “BaVarious Voices” concert in the Gasteig with Munich’s LGBTI* choirs. There’s a special bond between the singers in Ukraine and Munich, and it has given rise to new friendships. Qwerty Queer sings at the Pride events in Kyiv and Odessa, on the streets, and on the TV. Meanwhile, LGBTI* choirs have also been set up in Kharkiv, Vinnytsia and Kryvyi Rih. In addition to Qwerty Queer, visitors to this year’s festival can look forward to hearing Dorothy’s Friends, Midnight Descant, and Voice Is My Life. And Various Voices is picking up the tab for all of them, as it is for the Turkish choir 7 Renk Koro. Together we are strong.

In Ukraine, Qwerty Queer has led the way. “One time a couple of young people got talking to us on the street,” Olga says, recalling a time when they had no rehearsal room so they had to go outside. “‘Who are you?’ they asked. ‘Ah, Qwerty Queer. Isn’t that the choir for lesbians and gays?’ I still get goose bumps when I tell that story. They could easily have turned out to be our enemies,” she says. But instead they were fans – what a spot of luck!

What is Olga still aiming to achieve? She wants to see Qwerty Queer grow. Ukraine needs to see more LGBTI* choirs emerge. And, ideally, all of them should sing together. “That’s something I experienced in Denver at the GALA Choruses in 2016 and in Munich last autumn, when we joined with all the Munich choirs to rehearse Carmina Burana together. It really gets under your skin.”

Olga Rubtsova delights in success, she’s ambitious, and she can definitely be strict with those around her. “I like how they’re developing. Let’s not forget we’re a lay choir.” Recently, as a warm-up, they rehearsed the song “Embrace me” by Okean Elzy, a Ukrainian rock band. “We’d never managed to sing that song before, but this time we nailed it.” Olga cried. “It’s when things like that happen that I remember why I’m happy to put so much effort into doing what I do.”

Singing as a political act

Qwerty Queer consists of Olga, a few more Olgas, Olenas, Mykyta, Kateryna, Yevheniia, and others. Many of them have been members for years. They sing together and look out for each other. Mykyta’s boyfriend was recently conscripted into the army and is headed for the front line. Now the others are there for him, comforting the one who’s left behind when he’s sad and giving him encouragement when he frets. Fortitude!

In a country with no tradition of lay choirs, Qwerty Queer is so much more than just an ensemble. For the women and for Mykyta it’s somewhere they can call home, be themselves, and just sing. And Qwerty Queer provides identity. After a few months of being in the group, most members managed to come out to their families at home. And with each performance they give, they help to set straight the distorted perception of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals in the public arena. They dispel prejudices simply by being normal. “We are singing for our lives!” Olga says with a laugh. That’s what turns singers into activists. Music brings us together.

And in her private life? Olga could choose to go to the conservatory now. But to do that, she’d have to turn her whole life upside down again. It wouldn’t be easy. What does her mother say? Unusually, this time she’s staying mum. Perhaps Olga should make the most of it.

Back to overview

What’s Olga’s secret? She’s talented, she’s pragmatic, and on occasion she’s as stubborn as a mule. If she hadn’t singlemindedly pursued her dream, she wouldn’t be standing on the podium in the Gasteig today. Olga Rubtsova, 32 and from Odessa, always wanted to make music. But it’s something of a miracle nonetheless that she now directs a choir. The path she took to get there was anything but straightforward – not least thanks to her own mother.

Qwerty Queer, Ukraine’s first ever lesbigay choir, is still a very young ensemble: it was born in late 2014 / early 2015 of an idea that came from Various Voices in Munich, no less. (We’ll come back to that story later.) The group’s ten core members have a repertoire stretching from pop through to folk music; they sing both political songs and love songs. Most of their tunes come from the UK, the USA, Ukraine, and Russia. And the singers are young: almost all of them are under 30.

What’s Olga’s secret? She’s talented, she’s pragmatic, and on occasion she’s as stubborn as a mule. If she hadn’t singlemindedly pursued her dream, she wouldn’t be standing on the podium in the Gasteig today. Olga Rubtsova, 32 and from Odessa, always wanted to make music. But it’s something of a miracle nonetheless that she now directs a choir. The path she took to get there was anything but straightforward – not least thanks to her own mother.

Qwerty Queer, Ukraine’s first ever lesbigay choir, is still a very young ensemble: it was born in late 2014 / early 2015 of an idea that came from Various Voices in Munich, no less. (We’ll come back to that story later.) The group’s ten core members have a repertoire stretching from pop through to folk music; they sing both political songs and love songs. Most of their tunes come from the UK, the USA, Ukraine, and Russia. And the singers are young: almost all of them are under 30.

And so the Kyiv activists carried the idea back to Ukraine, where it came to bear fruit in Odessa. It was here on the Black Sea that Munich Kyiv Queer, which brings together activists from Kyiv and Munich, was due to put on an exhibition of Munich artist Naomi Lawrence August 2014. This was an ideal opportunity to present the Various Voices project at Queer Home, which is Gay Alliance Ukraine’s local meeting point. To whet the Ukrainians’ appetite, they offered to fly the choir that would participate in the choral festival in 2018 to Munich once each year, as a way of helping it to get going. Munich’s choirs had committed to help.

It didn’t take long to find some volunteers, and the then head of Queer Home in Odessa, Anna Leonova, already had a director in mind: Olga Rubtsova, who she knew from Queer Home. But Olga demurred: “It seemed to me to be too much responsibility,” she says today. In addition, she wasn’t even out. She managed to fend Anna off for half a year – even though Olga was absolutely destined for this role like no other.

And so the Kyiv activists carried the idea back to Ukraine, where it came to bear fruit in Odessa. It was here on the Black Sea that Munich Kyiv Queer, which brings together activists from Kyiv and Munich, was due to put on an exhibition of Munich artist Naomi Lawrence August 2014. This was an ideal opportunity to present the Various Voices project at Queer Home, which is Gay Alliance Ukraine’s local meeting point. To whet the Ukrainians’ appetite, they offered to fly the choir that would participate in the choral festival in 2018 to Munich once each year, as a way of helping it to get going. Munich’s choirs had committed to help.

It didn’t take long to find some volunteers, and the then head of Queer Home in Odessa, Anna Leonova, already had a director in mind: Olga Rubtsova, who she knew from Queer Home. But Olga demurred: “It seemed to me to be too much responsibility,” she says today. In addition, she wasn’t even out. She managed to fend Anna off for half a year – even though Olga was absolutely destined for this role like no other.

And that was how Qwerty Queer was formed. Of course, it wasn’t called that yet. Where did the name come from? QWERTY is the order of the letters on US computer keyboards. When they started searching online in social networks for people to join their choir, the women ended up doing lots of typing, and that’s where they got the idea. “Qwerty” stands for the regular, the normal. “Queer” for otherness, for diversity. So “Qwerty Queer” it was, then – a part of a whole, in all its colourfulness.

Olga started rehearsing with the three women – on a voluntary basis, of course. Over time, they were joined by more women, and later men too, and their repertoire expanded. When six of them travelled to Mainz in June 2015 with their Munich counterparts for the QueerTakte gathering of south German choirs, the Ukrainian singers really impressed everyone – including Mainz’s mayor, who was in the audience for a memorable performance of some of their songs.

And that was how Qwerty Queer was formed. Of course, it wasn’t called that yet. Where did the name come from? QWERTY is the order of the letters on US computer keyboards. When they started searching online in social networks for people to join their choir, the women ended up doing lots of typing, and that’s where they got the idea. “Qwerty” stands for the regular, the normal. “Queer” for otherness, for diversity. So “Qwerty Queer” it was, then – a part of a whole, in all its colourfulness.

Olga started rehearsing with the three women – on a voluntary basis, of course. Over time, they were joined by more women, and later men too, and their repertoire expanded. When six of them travelled to Mainz in June 2015 with their Munich counterparts for the QueerTakte gathering of south German choirs, the Ukrainian singers really impressed everyone – including Mainz’s mayor, who was in the audience for a memorable performance of some of their songs.

What is Olga still aiming to achieve? She wants to see Qwerty Queer grow. Ukraine needs to see more LGBTI* choirs emerge. And, ideally, all of them should sing together. “That’s something I experienced in Denver at the GALA Choruses in 2016 and in Munich last autumn, when we joined with all the Munich choirs to rehearse Carmina Burana together. It really gets under your skin.”

Olga Rubtsova delights in success, she’s ambitious, and she can definitely be strict with those around her. “I like how they’re developing. Let’s not forget we’re a lay choir.” Recently, as a warm-up, they rehearsed the song “Embrace me” by Okean Elzy, a Ukrainian rock band. “We’d never managed to sing that song before, but this time we nailed it.” Olga cried. “It’s when things like that happen that I remember why I’m happy to put so much effort into doing what I do.”

What is Olga still aiming to achieve? She wants to see Qwerty Queer grow. Ukraine needs to see more LGBTI* choirs emerge. And, ideally, all of them should sing together. “That’s something I experienced in Denver at the GALA Choruses in 2016 and in Munich last autumn, when we joined with all the Munich choirs to rehearse Carmina Burana together. It really gets under your skin.”

Olga Rubtsova delights in success, she’s ambitious, and she can definitely be strict with those around her. “I like how they’re developing. Let’s not forget we’re a lay choir.” Recently, as a warm-up, they rehearsed the song “Embrace me” by Okean Elzy, a Ukrainian rock band. “We’d never managed to sing that song before, but this time we nailed it.” Olga cried. “It’s when things like that happen that I remember why I’m happy to put so much effort into doing what I do.”