A Letter From the Front Lines

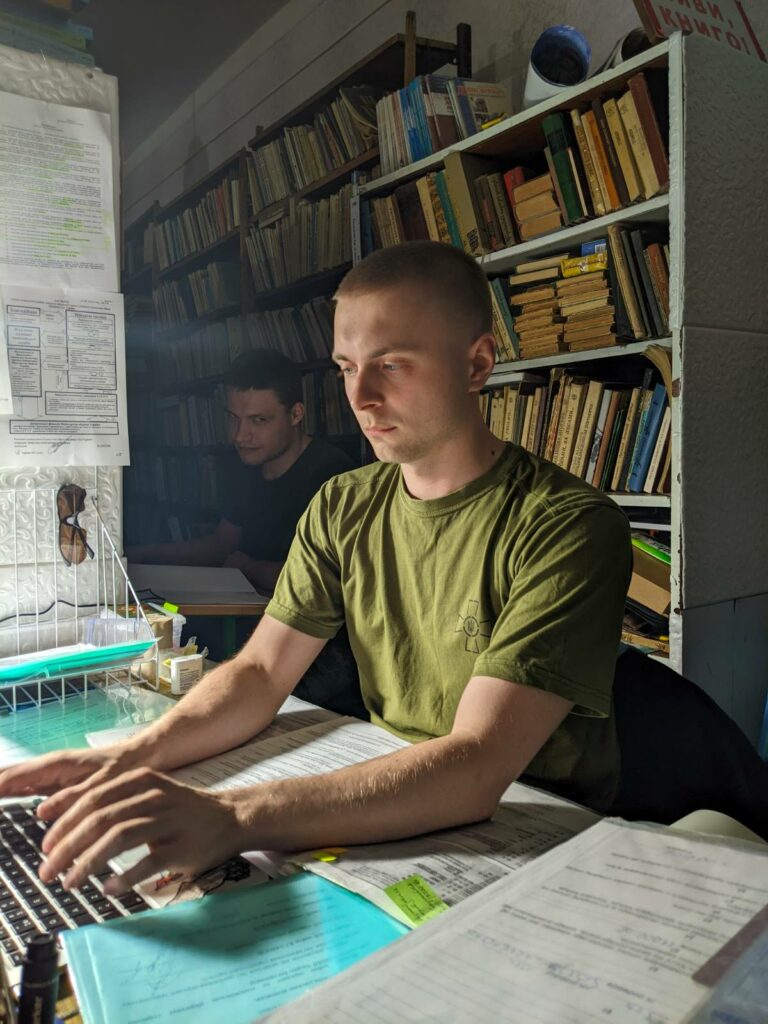

Petro Zherukha, a 27-year-old cisgender bisexual soldier, shares his journey amidst the chaos of war. Despite the dangers, Petro bravely confronts his identity, proudly displaying an LGBTIQ* chevron on his uniform to challenge discrimination and seek acceptance within the ranks. His story exemplifies resilience in the face of adversity. Our columnist Iryna Hanenkova has put down his story.

From the first days of the invasion, I joined the military. At these critical moments, everything seemed to lose its meaning, except for victory, which was directly associated with the future. For a moment, there was a feeling that there would be no future because we and our memories were being slaughtered. But it turned out that love for everything and faith were and will be stronger than any fear of death.

In the army, I serve in the supply unit and deal with everything related to transport. My military unit entered the front line quickly, so every second of doubt or lack of knowledge could become the end of us. Our logistics team worked almost around the clock. We debated whether to take cover during alarms or the sounds of explosions. We decided that we would work until the very last. If a missile hits the building where we work and we die, then so be it. And if not – it will explode somewhere nearby, then there is nothing to worry about, and therefore, all the more to continue our work. We could not afford any delays at work because it directly affected the provision for our fighters in positions.

My coming out was not related to the army, although I felt a direct threat to my life because the army was not the safest environment for me or anyone in general. My friend, who was directly involved in the creation of the draft law on registered partnerships, inspired me. The military system, on the contrary, systematically oppressed me.

Serving in the army is a quite challenging task. If you serve faithfully, that is. We wanted to strive to be good soldiers and dedicated all our energy, comfort, principles, personal space, funds, skills, knowledge, and even some fundamental human rights just to bring victory closer to us. We knew this system would never thank us so we accepted the fact that we would be anonymous benefactors, giving it everything we had to win this war.

I fought and still fight against the military system for my personality and my identity. I saw people lose parts of themselves, and their personalities, both in the army and at the front. I noticed that I also felt different and lost something of who I was before the army.

When I shared with my friends the idea that I might want to come out only to our group – they rejected me. I’m sure that’s because of the fear of the unknown. After the victory – they said, “not in time” – a golden saying that, sort to speak, so clearly describes the diagnosis of our society: to decide to postpone the desire to be happy right now. And I obeyed.

But when I found out about everything that my friend did for me and people like me in the army, I decided not to suppress my personality anymore, to stop being afraid of reactions, and openly talk about discrimination if it happens. And I opened up, perhaps, among the most conservative people and in the most dangerous conditions imaginable. As you understand, this happened in a war zone between brothers and sisters who have been fighting for more than a year; who are tired, exhausted, wounded, lost, and with weapons in their hands. My superiors were afraid that I might get shot. I didn’t believe it.

When I attached a chevron with an LGBTIQ* flag to my uniform, I was regularly “advised” to take it off, and I believe that someone was simply afraid of aggression towards me. Someone was uncomfortable, someone discriminated against me passively, and someone thought that I was discriminating against them.

However, I accepted it – I am uncomfortable for many, incomprehensible, new for perception, so it takes more effort to accept me. That’s why I serve with an LGBTIQ* chevron so that my military accepts me for who I am and forms boundaries and relationships with the real me. I want to brag about the fact that I am successful in this and feel that in this way I choose to strive to be happy right now.

This is how you can donate

INDIVIDUAL HELP Munich Kyiv Queer has its own fundraising campaign via https://www.paypal.me/ConradBreyer to support queer people in Ukraine who are in need or on the run. Why? Because not all LGBTIQ* are organised in the local LGBTIQ*-groups. This help is direct, fast and free of charge if you choose the option “For friends and family” on PayPal. If you don’t have PayPal, you can alternatively send money to the private account of Conrad Breyer, speaker of Munich Kyiv Queer, IBAN: DE427015000021121454.

All requests from the community are meticulously checked in cooperation with our partner organisations in Ukraine. If they can help themselves, they take over. If the demands for help exceed their (financial and/or material) possibilities, we will step in.

HELP FOR LGBTIQ* ORGANISATIONS To support LGBTIQ* in Ukraine we have helped set up the Alliance Queer Emergency Aid Ukraine, in which around 40 German LGBTIQ* Human Rights organisations are involved. All these groups have access to very different Human Rights organisations in Ukraine and use funds for urgently needed care or evacuation of queer people. Every donation helps and is used 100 percent to benefit queer people in Ukraine. Donate here

Questions? www.MunichKyivQueer.org/donations

Comments are closed.

Back to overview